Not The Prettiest Fossil But This Fossil Lobster Has An Amazing Tale To Tell

Eleventy-one* years ago exactly from today’s date (February 13, 1902) F. W. Stokes was painting images of Emperor Penguins, on Snow Hill Island at Admiralty Sound, Antarctica. Stokes was an American artist on the 1901-1903 Swedish South Polar Expedition. As Stokes hiked around the small island sketching icebergs, rocks, and penguins he picked up a small collection of fossils (about eight) lying loose on the islands talus-covered slopes and these fossils would become the first fossils from Antarctica to be described scientifically. He carried these fossils with him from Antarctica to the Falkland Islands where the rest of the team spent the winter. Stokes decided to leave the expedition and took a steamer to Montevideo*,* Uruguay and then traveled back to the United States and finally Chicago. He handed over the specimens to a well-known paleontologist at the University of Chicago, Dr. Stuart Weller.

Dr. Weller immediately recognized the significance of these fossils and published a brief nine page scientific article describing them by May 1903, less than six months after he was given them by Stokes. Dr. Weller became the first person to describe fossils from Antarctica. At this same time the rest of the Swedish expedition was trapped in Antarctica after their ship was crushed by ice. They survived by eating penguins and penguin eggs. An Argentinean rescues mission was not able to reach them until November of 1904. The expedition members upon arriving back in Sweden were surprised to find that Weller had already published on some of the fossils and even more dismayed that their Swedish expedition was mistakenly referred to as the “Belgian Antarctica Expedition” in Weller’s article (Weller, 1903, p.413).

In 1906 all of the Swedish Expedition’s scientific findings were published including a 52 page descriptions of the complete fossil fauna recovered from Antarctica in their publication Dr. Gunnar Andersson, a Swedish paleontologist on the expedition, notes:

“He (Stokes) collected some fossils specimens on Snow Hill Island during the two days in Febr. 1902 when the wintering party was landed. Though he had agreed not to communicate anything of the scientific results of the expedition, we found on our return that a description of his small fossil collection had been published.”

The Stokes Antarctica Collection (the 8 fossils picked up by Stokes) was donated to the University of Chicago’s Walker Museum, which eventually was donated to The Field Museum where these 8 fossils now reside. Dr. Weller gets credit for publishing the first scientific description of fossils from Antarctica, but the honor should have gone to Dr. Andersson.

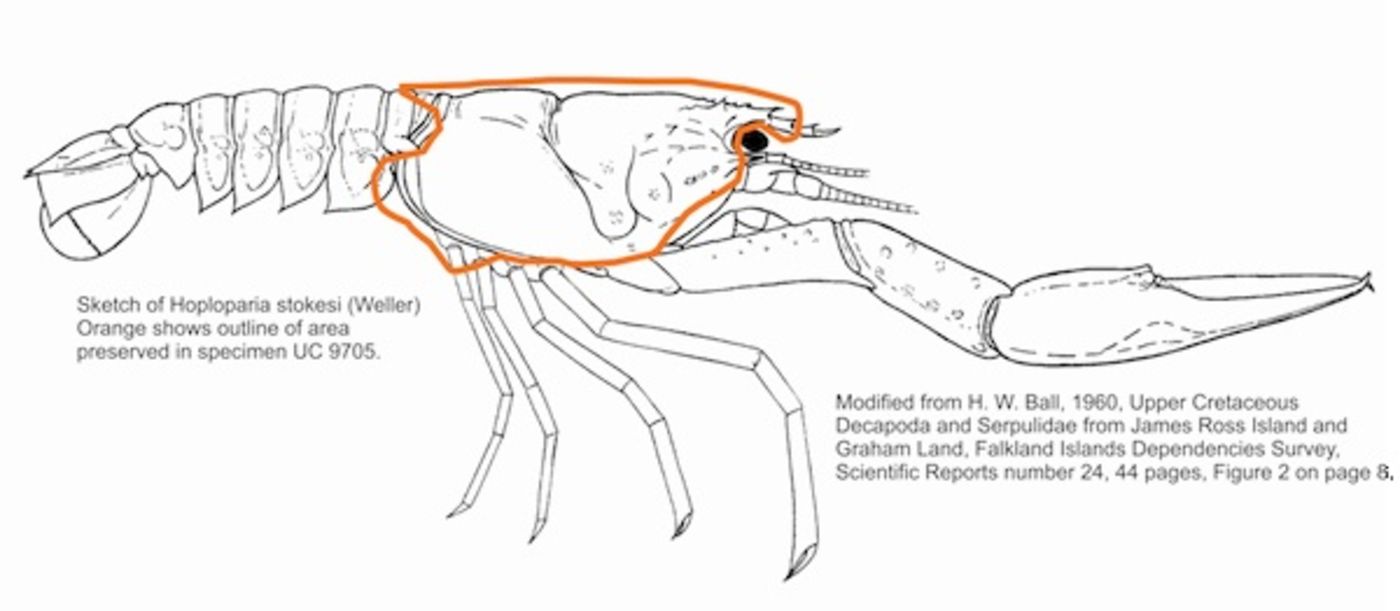

This small, broken lobster fossil Hoploparia stokesi UC 9705 is the first fossil to be described from Antarctica and was named in honor of F. W. Stokes. The fossil might not look like much but the data it has are important. It tells us that Antarctica was not always a frozen, ice-covered continent, but 100 million years ago a shallow sea covered it and lobsters, bivalves, gastropods (snails), and ammonoids lived in this sea. The lobster is similar to fossil lobsters collected in South America and India and this tells us that these areas all had shallow seas that were at least occasionally connected and these animals could migrate between these areas. The Field Museum maintains a collection of fossils not only for their aesthetic appeal and rarity, but primarily for the information that they can tell us about our planet and how it has changed over time.

References:

Andersson, J. G. 1906, On the Geology of Graham Land, Bulletin of the Geological Institution of the University of Upsala, Volume 7, Pages 19-71, pls 1-6.

Ball, H. W., 1960, Upper Cretaceous Decapoda and Serpulidae from James Ross Island and Graham Land, Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, Scientific Reports, number 24, 44 pages.

Stokes, F. W. 1903, An Artist in the Antarctic, The Century Magazine, August Issue, pages 521-528 (p. 525-526 = quotes).

Weller, S. 1903, The Stokes Collection of Antarctic Fossils. Journal of Geology, Volume XI, number 4. May-June. p. 413-419.

- 111 years for non-Hobbitt readers

An Artist in the Antarctic, By Frank Wilbert Stokes, with pictures by the writer, the first artist to bring paintings from the Antarctic.

“Wednesday, February 12. Bright and sunny. We were at last in Admiralty Inlet. A little space in the dun-colored mountains to the left of a great glacier was pointed out where we purposed landing to find a site for the winter station. About seven in the morning we rowed ashore. The boat danced over the blue waves, and the air from the ice was keen. It was delicious to drink in the sunlight from the pure azure and the sparkling sea. After a thirty minutes’ row we came to a low shore, along which was scattered a fringe of huge ice-blocks of turquoise and cobalt blues, showing at their tops fantastic forms of sea-water arrested and frozen during the recent tempest. After choosing the site, I climbed up a hill and saw that the land looked like an island, with a strait of open water to the northwest of the glacier, and two small islands. We returned to the Antarctic, breakfasting at ten o’clock. Preparations were made at once to land stores for the winter party. The setting sun was the most dazzling gold, in a setting of pale yet rich golden salmon-pink at the horizon, merging into turquoise-pink, yellow, delicate violet, and finally into the deep blue turquoise - cobalt of the zenith.

The sun flashed its blinding gold across a perfectly calm seal the glacier to the left being a deep purple cobalt blue, tinctured with the sun’s madder and gold, while the cliff on the right was a deep yet grayish purple and madder-brown, and the ice-floes at a little distance showed pure turquoise tints of cobalt and delicate rose. The sky was Eastern in its aspect, and somewhat characteristic of Egypt.

Thursday February 13. Bright and beautiful sunlight. All was noise, bustle, and confusion. Two whale-boats lashed together and covered with a platform were used to carry goods and provisioning ashore. The frame of the winter house was put together. The decks were slippery with grease and filth. Poor dogs! In a measure they had become accustomed to their floating home, but none of them liked it. The Eskimo dogs were aware that land was near, and their tails were screwed up tight over their backs in consequence.”